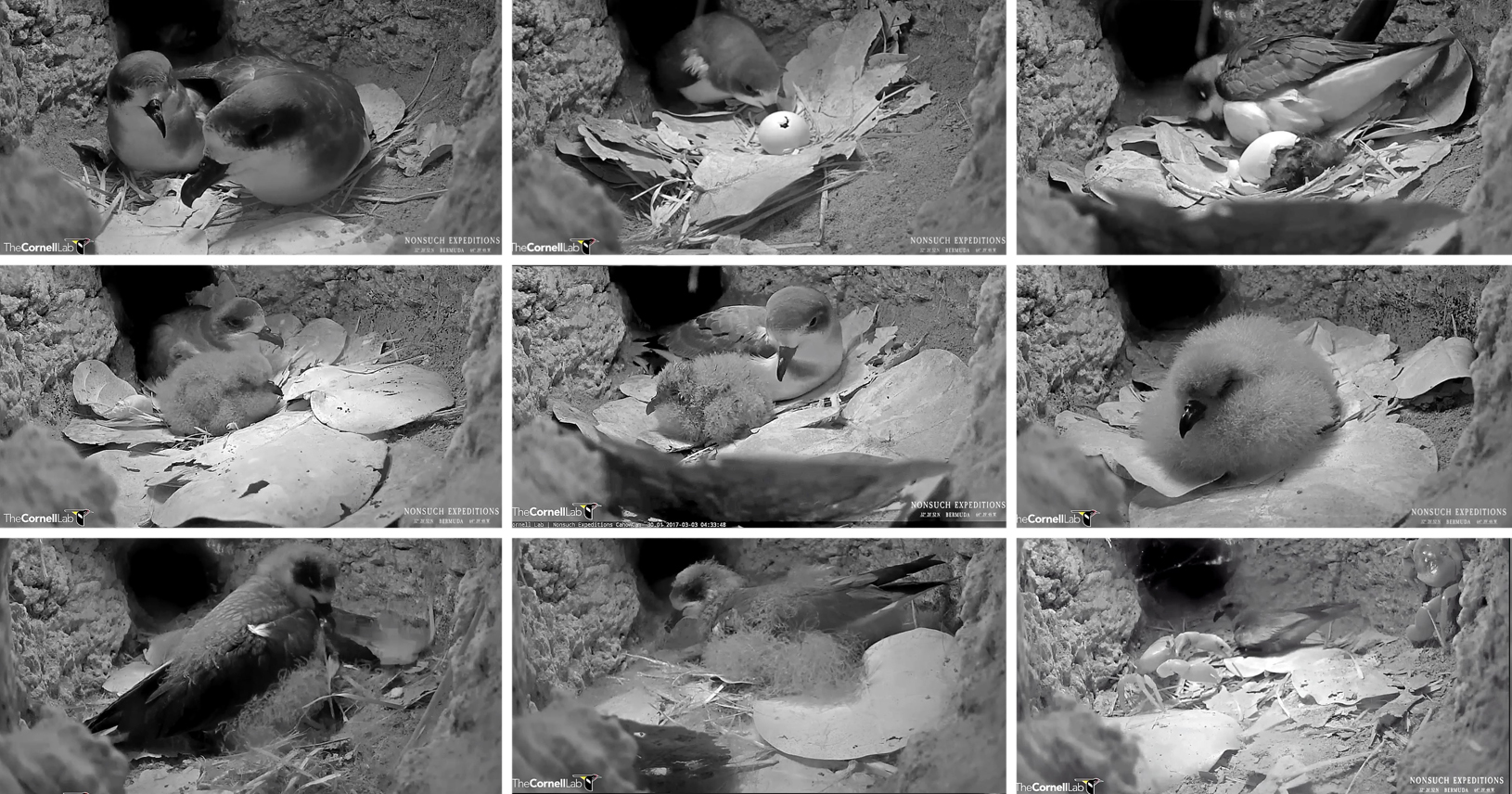

Watch the newly hatched Cahow chick have its first meal. It's parent caught squid, krill and small oily fish on a several hundred mile feeding run to the cold waters of the Atlantic, north of the Gulf Steam. (be sure to turn on audio)

Hello World! We Have a new Cahow Chick

March 2nd 8:30 AM | After an extended hatching process our Chick has finally fully emerged from the egg!

Jeremy had first observed "dimpling" on the egg during a nest check 2 days prior on February 28th (learn more) indicating the start of the hatching process and by midday on March 1st a small "pip" hole had been observed by the Cornell Team monitoring the streaming video. At 7pm as the pip hole was slowly getting larger the male parent barged in to take over incubation from the female who had been on duty since February 19th and after a few exchanges she retuned out to sea to feed and re-energize.

Throughout the long night as the Bermuda and Cornell Teams watched along with numerous other followers from around the world, the chick in the egg and the father went through cycles of sleeping and bursts of activity as the chick tried to break free with the father nibbling at the edges of the hole to help it get out.

As dawn approached the Team was starting to get concerned that the chick was taking too long to emerge as once the first pip has been made the egg and chick start dehydrating and if the process takes too long this can prove fatal.

Two years ago a similar situation had occurred and thanks to the CahowCam Jeremy was able to track exactly how long the process was taking and then intervened when it became apparent that the chick might not survive. In that case he used sterilized surgical snips to very careful enlarge and weaken the edges around the existing pip hole which allowed the chick to successfully hatch after a few hours, fledging out to sea normally 3 months later.

Therefore on the morning of the 2nd, despite the building seas from incoming winter storm Riley he was preparing for a similar rescue mission out to Nonsuch (as the incoming weather would have restricted access to the island for the following few days making urgent intervention impossible) however fortunately at 8:30 AM Bermuda time the chick was finally seen fully emerging from the egg!

2018 CahowCam egg in early stages of hatching.

It was confirmed that the egg was in the early stages of hatching, with the chick actively moving in the egg and having produced a number of "dimple cracks" half-way around the large end of the egg.

This process can vary greatly in time, and hatching could be anything from several hours to a couple of days away.

Read moreFirst Two CahowCam Chicks Have Returned!

Both "Backson" from 2013 and "Lightning" from 2014 have returned after surviving the odds of their first few years alone at sea.

Even more incredibly Backson, now confirmed to be a female has laid her first egg with her mate in a nest that they have been prospecting in Translocation Colony B on Nonsuch Island.

Jeremey Madeiros | Returns of 2013 and 2014 “CahowCam” Cahow Chicks

The present 2017-2018 Cahow breeding season has already produced a number of surprises and developments in the Recovery Program for Bermuda’s critically endangered National Bird, the Cahow or Bermuda Petrel, one of the rarest seabirds on Earth.

Since 2013, the team has been video monitoring one of the deep Cahow nest burrows on the Nonsuch Island Nature Reserve, to help fulfill one of the primary objectives of the Cahow Recovery Program, that of public outreach and education.

In 2013 an infrared video "CahowCam" (developed by LookBermuda as part of the Nonsuch Expeditions) was installed for the first time in the R832 Cahow burrow at the “A” Cahow colony on Nonsuch Island. This chick hatched on the 13th of March, 2013, and developed normally over the next 3 months, reaching a peak weight of 393 grams on the 6th of June. It then rapidly developed its adult feathers and carried out 6 nights of pre-departure exercising activity, coming out of the nest burrow at night to exercise and strengthen its flight muscles and imprint on the nest colony site. During this period, it “slimmed down” to a normal departure weight of 293 grams, fledging out to sea on the night of 16th June, 2013. The chick was then not seen for several years, living out on the open ocean and learning how to find and catch food, avoid predators, and learn how to survive on one of the harshest environments on Earth; the North Atlantic Ocean.

Over 4 years later, on the 5th December, 2017, I was carrying out a check of nest burrows at the “B” nesting colony on Nonsuch Island. This second site has had Cahow chicks translocated to it since 2013, in an effort to establish a second nesting colony on the island, following the success of the first, “A” colony. Earlier, on October 30th, one of the nests at this second site was prospected for the first time, with a male Cahow found in it that had been translocated to this site in 2013.

On this day, I could see a Cahow in the burrow that had already begun building a grass nest, and when captured and brought out of the nest for examination, I could see that it was one of the birds that I had previously banded as a chick. The band number, E0500, also seemed oddly familiar, so I checked my records and confirmed that this bird was indeed Backson, our first CahowCam video star! It was very satisfying to see that Backson had not only survived its risky adolescent period at sea, as typically only about one-third of fledging Cahow chicks survive this period to return as adults, but that it had already paired up with another Cahow.

Normally, new pairs of Cahows do not produce eggs during their first year together, but on the 22nd January, 2018, I found Backson incubating a newly laid, fertile egg in this nest burrow. I was also able to confirm for the first time that Backson was indeed a female. As of this time, we are just waiting to see if this egg hatches, which would happen in the next two weeks or so.

As if all this was not exciting enough, on the 20th January, 2018, I had discovered another newly returned Cahow, prospecting inside a nest burrow on one of the original small nesting islets. Upon examination of its band number, this bird turned out to be the second CahowCam chick, which was named “Lightning” by Sophie Rouja in the 2014 nesting season. This bird, from the R831 nest on Nonsuch Island, hatched on March 2nd, 2014, reached a peak weight of 422 grams on May 6th, and fledged to sea on May 27th, 2014. (This bird’s name was prophetic, as the CahowCam was knocked out twice by lightning strikes on Nonsuch Island while the chick was developing, which has led to a fair weather naming policy). So far, this bird has not attracted a mate to its new nest site, but we will continue to monitor for new developments in this regard as the season progresses.

Jeremy Madeiros, Senior Terrestrial Conservation Officer, Dept. of Environment and Natural Resources

2018 CahowCam Egg has been laid, officially launching the 6th Live Streaming Season!

The 6th CahowCam Season was officially started when our star Cahow laid her egg at 4:27 am LIVE on camera from Nonsuch Island.

J-P Rouja | Nonsuch Expeditions Team Leader:

"Our CahowCam broadcasting LIVE from the underground nesting burrow on Nonsuch Island was being monitored in anticipation of her return (which Jeremy had predicted to be that night) however the Bermuda Team had just signed off for the night when she burst in at 3am. The Cornell Team currently in Hawaii installing an AlbatrossCam were still watching along with many of our regular followers so promptly tweeted and alerted us of the event.

UPDATE | The male returned at 10pm on the 13th to take over incubation duties so that the female could head back out to sea for a few weeks to feed and re-energize.

Last Season through our Cornell partnership we reached 600,000 viewers who consumed 8.5 million minutes of video over the 5 month nesting season including thousands of people watching when the egg hatched in March. As we expand the project including new ways for our viewers and students to engage we expect to greatly exceed those numbers this Season."

To watch the LiveStream please visit Nonsuchisland.com

If you would like to be notified of this and other significant Cahow milestones sign up for our Newsletter and select the CahowCam alert option. If you are already a subscriber open a recent Newsletter and adjust your preferences to select the CahowCam alert option.

Jeremy Maderios | Chief Terrestrial Conservation Officer:

“Last year, the male returned by Jan. 15th, and took over incubation for the next 2 1/2 weeks while the female returned back out to sea to feed and regain her strength. The pair then alternated incubation duties until the egg hatched on March 2nd, 51 days after being laid.

After a record-breaking nesting season last year with 61 chicks fledging out to sea, we seem to be on track for breaking even more records this year. As of January 12th, the Senior Conservation Officer had confirmed that about two thirds of the breeding pairs on the nesting islands had so far returned and were incubating eggs, including 11 breeding pairs on Nonsuch Island. The remainder should hopefully return over the next 2 weeks. The majority of incubating adult Cahows he examined were heavier than normal, with some male birds approaching 500 grams in weight. This indicates that the birds had found good feeding conditions north of the Gulf Stream over the last month.”

Cahow return imminent, countdown to the laying of one Of the rarest eggs on the planet!

Last season the female Cahow (seen above) returned to the CahowCam burrow on January 11th, and promptly re-arranged the nest material before laying her single egg 53 minutes after her return.

UPDATE | 2018 - January 12th 4:27 am after returning at 3:05 am the female has laid her 2018 egg! Details to follow...

Follow our LiveStream to watch this rarest of events LIVE

If you would like to be notified of this and other significant Cahow milestones sign up for our Newsletter and select the CahowCam alert option. If you are already a subscriber open a recent Newsletter and adjust your preferences to select the CahowCam alert option.

Jeremy Maderios | "Last year, the male returned by Jan. 15th, and took over incubation for the next 2 1/2 weeks while the female returned back out to sea to feed and regain her strength. The pair then alternated incubation duties until the egg hatched on March 2nd, 51 days after being laid.

After a record-breaking nesting season last year with 61 chicks fledging out to sea, we seem to be on track for breaking even more records this year. As of January 10th, the Senior Conservation Officer had confirmed that about half the breeding pairs on the nesting islands had so far returned and were incubating eggs, including 9 breeding pairs on Nonsuch Island. The remainder should hopefully return over the next 2 weeks. The majority of incubating adult Cahows he examined were heavier than normal, with some male birds approaching 500 grams in weight. This indicates that the birds had found good feeding conditions north of the Gulf Stream over the last month."

Critically Endangered Bermuda Skink visits CahowCam Burrow

A Bermuda Skink was recently filmed visiting the CahowCam burrow as we wait for the female to return to lay her egg. Historically, they have a long-standing, important relationship with the Cahows as they help keep the nests clean.

Jeremy Madeiros | " The management and protection of the small nesting islands where the endangered Cahow nests also has an added bonus, in that this also protects a number of other native and endemic plant and animal species. One of the most significant of these is the critically endangered Bermuda Skink, which used to be common across most of Bermuda, but is now found only on isolated offshore islands and in a few small, fragmented populations in coastal locations such as Spittal Pond. It is now one of the rarest lizard species on Earth, and is found on at least 4 of the small islands where the Cahow nests.

For many years, I have observed Skinks in Cahow nest burrows on these islands, often when the Cahows themselves are in residence. They seem to tolerate each other's presence, and there is evidence that the both species benefit from the association, with the Skinks using the burrows for shelter, eating insects, spilled food, infertile eggs etc., keeping the burrows clean and disease-free for the Cahows. It was known that a small colony of Skinks lived in the Cahow colony on Nonsuch, with surveys indicating that this population may have increased in the last couple of years; this was the first time that we had been able to record a skink visiting the CahowCam nest."

Mark Outerbridge | MSc, PhD, Wildlife Ecologist, Government of Bermuda

History

· The skink is Bermuda's only endemic, four-legged, terrestrial vertebrate (in other words they are the only living land animal with a backbone to have reached Bermuda before humans, and they exist nowhere else in the world)

· Skinks are descended from a species that once inhabited the eastern U.S.A. and subsequently dispersed over oceanic waters to Bermuda (Brandley et al., 2010)

· Fossil evidence indicates that skinks were living on Bermuda more than 400,000 years ago but paleontological and geological evidence suggest they may have been present here for 1-2 million years (Olsen et al., 2006)

· Skinks were historically described as being very common, frequenting the old walls and stone heaps in the cedar groves of Bermuda (Jones, 1859). Now, most of the fragmented populations are only found within the rocky coastal environment.

Ecology

· Adult skinks grow to 15-25 cm in length and weigh between 13-22 g. Hatchlings are 6 cm long, weigh about 1 g and have bright blue tails (which fades as they grow older).

· Skinks are thought to live for 20+ years

· Skinks are diurnal and are most active mid-morning and late afternoon

· Active year-round (they don’t brumate – reptile equivalent of hibernation - during the winter months)

· Ground dwelling species (don’t climbing trees)

· Omnivorous diet; insects, arthropods, prickly pear fruit and carrion from burrow-nesting birds (e.g. cahows and longtails)

· Oviparous species (i.e. egg laying). Nesting occurs in May and June (3-6 eggs typically laid on the soil under rocks). Females guard their eggs.

· Hatching begins in July and August after a 5 week incubation period.

Threats

· Bermuda’s skinks are now on the brink of extinction. They are listed as critically endangered and receive protection under the Protected Species Act.

· Habitat alteration and predation from introduced species are considered to be the main causes of population fragmentation and decline

· The total island-wide (hence global) population was estimated to be 2300-3500 individuals (Edgar et al., 2010)

· Skinks have been reported from at least 24 separate locations across Bermuda (Edgar et al., 2010) but the greatest concentration is found within the Castle Islands Nature Reserve

· Various population assessments have been undertaken over the past two decades. Some of the fragmented populations consist of only 50 individuals while others number in the hundreds. The largest population is currently found on Southampton Island (estimated 500 skinks).

Nonsuch skinks

· Surveys conducted on Nonsuch over the past 50 years suggest the population is declining and those skinks that remain are only found in a few locations on the island.

· In the early 1960s, the vegetation on Nonsuch was mostly grass and coastal shrubs – ideal habitat for skinks (dense ground cover for concealment from predatory birds and rich in insect prey)

· The reforestation efforts that have occurred since the 1960s drastically changed the interior of the island, making it less favorable as suitable skink habitat (Wingate, 1998)

· The creation of the two cahow nesting sites is expected to benefit the skinks; as the cahow colony grows on Nonsuch, so too should the skink colony.

Penguins take flight for their annual New Years migration from the North to South Pole.

Watch BBC video of Penguins taking flight for their return to the South Pole. They migrate to the North Pole for Christmas to assist with security measures and then fly back to the South Pole just before New Years Eve, as explained in this Wikipedia article.

They have also been observed doing a non-flyby of Mangrove Bay in Bermuda on the Sunday preceding the first Monday in August, at exactly 1:58pm, following 2 days of non-resulting Cricket.

The Bermuda sightings are believed related to a harmonic disturbance in the Bermuda Triangle and coincide with an annual Non-Mariners event that celebrates the non-sinking of unseaworthy vessels, and the sighting of unflightworthy birds.

Happy New Year :)

Happy Holidays from the Nonsuch Expeditions Team

Wishing you and yours the Happiest of Holidays!

The 1st CahowCam Star has returned!

As a Nonsuch Christmas present, Backson the Star Cahow chick from the first CahowCam season has returned to Nonsuch Island after 4 years at sea.

Jeremy Madeiros: “Backson” is back!

"It is always an exciting and satisfying feeling when something that was started years ago finally comes to fruition. I had that feeling on December 5th, when I was on Nonsuch Island making a check of Cahow nest burrows. Taking advantage of a break in the windy weather, I first checked the original “A” colony site, where Cahows moved here as chicks between 2004 – 2008 have returned, chosen nest burrows, and attracted mates, establishing a new nesting colony which is now up to 16 breeding pairs. I then moved on to the 2nd, “B” colony site, where I have been moving chicks since 2013, and where the birds first began to return earlier this year. In one of the nest burrows, I had already recorded a returning male bird on November 12, 2017, that had been translocated to a nearby nest at this site in 2013. Upon opening the nest lid, which enables me to check inside the nest without unduly disturbing the birds, I saw an adult Cahow sitting quietly on a partially completed nest. At first, I thought it was the male bird, but upon turning the bird over to read the number of the band fitted to the left leg, I saw an unfamiliar number, E0500, which raised alarm bells as being significant in some way.

Upon returning to the mainland, I checked my computer’s banding files, and confirmed that the bird in question was in fact our first CahowCam, video star Cahow chick, which hatched on and fledged to sea from Nonsuch Island back in 2013. This chick was named “Backson”, and was born to two parents who were both translocated as chicks to Nonsuch Island in 2005, one from the Horn Rock C22 nest, the other from Inner Pear Rock D4 nest. These birds started to nest back on Nonsuch at the “A” colony site in 2010, and Backson was their third chick. Backson hatched on the 13th March, 2013, and fledged out to sea on the 15th June of that year. After spending the last four years maturing out on the open North Atlantic Ocean, backson has returned, turned out to be female, and has already chosen a mate over at the “B” colony site. We will be watching with interest over the rest of the nesting season as this new pair becomes established, and hopefully will produce their first egg in the next, 2018-2019 nesting season."

Jeremy Madeiros, Senior Terrestrial Conservation Officer, Dept. of Environment and Natural Resources

She was named by Junior Explorer Sophie Rouja based on a Winnie The Pooh story in which a note from Christopher Robin saying he would be "back soon" was misread as "Backson". This ultimately proved to be an appropriate name as Backson was indeed back soon.

Merry Christmas Everyone!

Great start to 2018 Cahow Nesting Season

The 2018 Cahow Nesting Season is off to a great start with a record 125 nesting pairs having been identified thus far.

Watch the Video Update with Senior Terrestrial Conservation Officer Jeremy Madeiros as he conducts a health check with our CahowCam Star then read his Cahow Nesting Season Update below.

Cahow Nesting Season Update | Nov 15th 2017

Although we will not know for certain until the birds lay their eggs around the beginning of January, 2018, best indications so far are that there are123 to 125 breeding pairs of Cahows this year. A pair is considered a breeding pair only if it produces an egg, whether it hatches or not. Newly establishing pairs often "go through the motions", court, build a nest together and mate, but often do not produce an egg during their first year together, and so are not considered a breeding pair for that year.

In addition, a small number of established pairs may have produced successfully fledging chicks for several consecutive years, but then become exhausted (and many of us know how exhausting raising a child can be!). If their body condition and weight falls beyond a certain point, they may meet at the burrow, build a nest, but take a "sabbatical year" off and not produce an egg that year. This usually enables them to recover and resume egg laying/chick rearing the following year.

The most exciting developments this nesting season will be to follow the progress of the first Nonsuch-produced Cahows during their first nesting season. To explain, Cahows were eradicated from Nonsuch and all the larger islands of Bermuda as early as 1620, due to hunting by the early settlers and predation by introduced mammal predators, including rats, cats, dogs and pigs. Cahows were only re-introduced to Nonsuch during the period 2004-2008, when chicks were moved or translocated from nests on the 4 original tiny half-acre nesting islets (which are suffering increasing erosion from hurricane waves and sea-level rise). These chicks were moved into artificial concrete burrows on Nonsuch and hand-fed on squid and fish until they fledged to sea, imprinting on Nonsuch rather than their original natal island. After spending 3 to 5 years at sea, these birds then returned to Nonsuch as young adults, paired up and started nesting in the same artificial burrows. The first chick to hatch on Nonsuch since the 1620s fledged to sea in 2009, and this new colony has now grown to 16 breeding pairs, producing a total of 54 chicks in the last 8 years. The first two of these Nonsuch-born chicks returned to Nonsuch in the 2016-2017 nesting season, and should produce their first eggs in the 2017-2018 nesting season.

This first translocation has been so successful that a second translocation project was started in 2013, moving chicks to a second group of artificial burrows at a different location on Nonsuch. The first translocated birds from this "B" site returned to the new location in 2017, and 2 new pairs may produce their first eggs at this new site in the upcoming season.

More updates & developments will be provided as the nesting season progresses.

All the best, Jeremy

Jeremy Madeiros | Senior Conservation Officer (Terrestrial) | Dept. of Environment and Natural Resources | BERMUDA

CahowCam 2017 Video Highlights

This past season 8.5 million minutes of CahowCam video were watched by our viewers from around the world, see highlights below (be sure to turn on audio using button in lower right of player).

CahowCam viewers watch more than 8 million minutes of video during 2017 nesting season.

The Nonsuch Expeditions CahowCam has now ended its 5th season broadcasting live from the underground Cahow nesting burrows on Nonsuch Island. This year its new partnership with the Cornell Lab of Ornithology resulted in 600,000 views for a total of 8.5 million minutes of video being viewed by scientists, students and followers from around the world.

Jeremy Madeiros, Senior Terrestrial Conservation Officer and Cahow Recovery Program Manager: "The Cahow Recovery Program represents a long-term commitment by the Bermuda Government towards the conservation and recovery of the island's National Bird. it represents one of the most successful programs for the recovery of a critically endangered species, and has endeavored to make use of new technology and management techniques whenever possible. Public outreach and education is one of the main objectives of the recovery program, and the CahowCam project and partnership with the Nonsuch Expeditions has contributed greatly to the achievement of this objective. In addition to bringing the story of the Cahow's survival and recovery to an international audience, it has enabled previously unknown aspects of the breeding biology and behavior of the species to be observed."

Charles Eldermire, Bird Cams Project Leader, Cornell Lab of Ornithology: "This season working with Nonsuch Expeditions to showcase the Cahow to a broader audience was a great success, reaching hundreds of thousands of viewers and raising awareness about the ongoing need for investment in the cahow's future. The foundation we laid through our partnership this year will allow us to continue improving the quality of the online experience in future years, and to further highlight the efforts of the Bermuda Department of Environment and Natural Resources."

Jean-Pierre Rouja, CahowCam designer and Nonsuch Expeditions Team Leader: "This project is a perfect example of how we aim to combine technology and media to assist and participate in conservation, research and educational outreach. What started out as a media-driven educational outreach project has now evolved into an extremely effective conservation tool, contributing greatly to the protection and recovery of the species."

There have been many examples over the past few seasons where the 24/7 live view of the up until now unknown nesting behaviors of one of the rarest seabirds on the planet is allowing the Team to re-write what is known about their behaviors and how they interact with each other as a colony.

The CahowCam stream has also allowed the Team to effectively crowdsource the monitoring of the 24/7 feed enabling viewers from around the world to watch, log and capture significant events that would have otherwise been missed.

Summary of 2017 Record Breaking Cahow (Bermuda Petrel) Breeding Season

Compiled by: Jeremy Madeiros, Cahow Recovery Project Manager, Senior Terrestrial Conservation Officer, Department of Environment and Natural Resources, BERMUDA GOVERNMENT

The most recent nesting / breeding season for the Critically Endangered Bermuda petrel, or Cahow, which is Bermuda’s National Bird and one of the rarest seabirds on Earth, began in late October 2016, and ended on the night of 27/28th June, 2017, when the last Cahow chick fledged out to the open ocean, not to return for several years. The Cahow is endemic or unique to Bermuda, nesting no-where else on the planet. It is pelagic, spending most of its life in the middle of the ocean, and returns to land only to breed, laying a single egg annually. It nests on only 6 small islands totaling only 20 acres, in the Castle Harbour Islands Nature Reserve, where it is protected by wardens and is the subject of an intensive management program.

Overall, during this breeding season, the Cahow has continued its positive upward trend in both the number of established breeding pairs and overall size of the population, and in the number of successfully fledged chicks being produced by the nesting pairs.

When active management of the Cahow and its tiny offshore nesting islands began around 1960, the entire population consisted of only 17 to 18 breeding pairs, producing a total of only 7 to 8 chicks annually. The population faced many threats and challenges, including predation by introduced rats swimming out to the nesting islands, lack of suitable deep nesting cavities, nest competition by the larger White-tailed tropicbird or Longtail, which took over nest burrows and killed the defenseless Cahow chicks, and light pollution from the nearby Naval Air Station (now Bermuda International Airport), which disrupts the night -flying cahow and disorients the chicks when they depart to sea.

The 2017 nesting season saw the Cahow nesting population increase to a record number of 117 established breeding pairs (those that produced an egg, whether it hatched or not). In addition, a record number of 61 chicks successfully fledged out to sea (the first time the number of fledged chicks has exceeded 60). These numbers have probably not existed since the 1600s, when the formally abundant Cahow was decimated by the arrival of human colonists on Bermuda, through overhunting and predation by introduced mammal predators such as pigs, rats, cats and dogs.

In addition to the encouraging continued increases in breeding pairs and fledging chicks, a record number of over 10 newly establishing, prospecting pairs was recorded, most of which should produce their first eggs and come “on-line” as breeding pairs next season.

Since one of the major threats facing the Cahow has been erosion and damage to their original tiny breeding islands by repeated hurricanes, which produce huge waves that completely submerge the smaller islands and rip huge chunks of rock away. Their small size also severely limits the number of breeding Cahows that can nest on them. To address this, one of the main objectives of the Cahow Recovery Program has been to establish new Cahow nesting colonies on larger islands that are safe from hurricane erosion and have more room to enable the Cahow population to grow. The islands also must be constantly managed and wardened to eradicate predators such as rats, and control human access to prevent disturbance.

Nonsuch Island was chosen as the site to establish a new Cahow nesting colony, as it is managed to exclude rats and other invasive species and is the site of a warden’s residence. Cahows were eradicated by the early colonists on Nonsuch, and had not nested on the island since the 1620s. Translocation is a technique in which chicks are removed from their original burrows on the smaller islets and moved to artificial burrows on Nonsuch, where they are hand-fed daily and allowed to imprint on and fledge from their new site. Cahow chicks were moved for 5 years during 2004-2008 to Nonsuch and fed until they fledged to sea. This technique worked and almost half of the translocated birds returned 3 to 6 years later to choose nest burrows and mates. By 2017, the number of nesting pairs at this new colony site increased to 16, with 8 chicks fledging from this area.

This project worked so well that in 2013 a second translocation program was started, to establish a second colony at a different location on Nonsuch. During the 2017 season, 14 Cahow chicks were translocated to Nonsuch, bringing the total number of chicks moved to this second site up to 65. In addition, during 2017 the first three Cahows moved to this site as chicks during 2013 and 2014 returned and started to occupy nest burrows at this second site, with one new pair confirmed, and it seems likely that this signals that the formation of a second new colony is underway.

Junior Explorer Sophie names "Shadow" the 2017 CahowCam Star.

Other threats to the Cahow that have been encountered include the invasion of Nonsuch by rats swimming over from the main island during 2016. These were eradicated by the use of rodenticide bait by November 2016, but this has highlighted the need for constant monitoring and vigilance to prevent further invasions by rats swimming out to the nesting islands. In addition, hurricane “Nicole” hit Bermuda directly in October 2016, submerging two of the smaller nesting islands but causing only limited damage. In early June 2017, one of the translocated chicks was stung to death by a swarm of honeybees that occupied its nest burrows, but this swarm was removed shortly after by the Government Agricultural Officer.

Despite these threats, the Cahow population has continued to increase and recover from the edge of extinction. Due to the Recovery Program and the intensive management and control of threats to the species, the future of Bermuda’s unique National Bird looks increasingly positive.

During this Season, the Nonsuch Expeditions CahowCam, now in partnership with the Cornell Lab of Ornithology streamed 8.5 million minutes video, to scientists, students and followers around the world. The real-time, 24/7 window into the Cahow's underground nesting chambers is allowing the team to confirm and in some cases re-write what is know about the Cahow's nesting habits and is contributing greatly to the recovery of the Species.

Stormy the "Loneliest Petrel" battles land crabs and wins!

In the early hours of July 3rd the CahowCam documented its' new resident, a very lost Storm Petrel holding his ground against two native red land crabs during a home invasion. Now named "Stormy" he is back for the second year attempting to attract a mate to the recelenty vacated Cahow burrow on Nonsuch Island. This year he first arrived in early June and as last year seems to have stayed for about a month, building a nest and calling out nightly from the entrance for a mate, before giving up. If he returns the team plans to band him and possibly help attract a mate.

These land crabs use their pinchers primarily for defensive purposes and usually scavenge the abandoned nests helping to clean them out at the end of each season. Stormy was clearly not worried and bit one of them before they gave up and left.

CahowCam viewer alerts team to flesh eating worm landing on Cahow chick.

A case study of Crowdsourcing the monitoring of the CahowCam and other Wildlife Cams.

The Nonsuch Expeditions CahowCams have once again this year been live streaming for 6+ months from the underground Cahow burrows on Nonsuch Island. Whilst these 24/7 video streams present many opportunities to learn more about our subjects, it is impossible (and unrealistic) to expect our small team to be monitoring them 24 hours a day, 7 days a week for 6+ months, and invariably significant events are missed.

This year our online viewers watched over 8.5 million minutes of CahowCam video over the 6 month period, all logging in when their schedules permit from different time zones around the world. This resulted in there being multiple if not hundreds or thousands of viewers online at any one point in time, and given the right tools they were able to log and and report significant events to us which we could then re-confirm by going back to the video archive being created at Cornell.

As a perfect example, on March 20th 2017, at 2:50 am local time, a planarian flatworm (possibly the snail eating variety) dropped from the roof onto the back of our Cahow chick. Our local Team was online but not watching at that exact moment, however one of our regular viewers who lives in Japan, was not only watching but recognized that this was something to possibly be concerned about and tweeted to us and other followers tagging our @BermudaCahowCam Twitter account including video frame grabs showing the intruder.

Bermuda is known to have three varieties of flatworms, two of which are flesh eaters that will for example kill and eat snails. The variety known to be on Nonsuch targets primarily earth worms, however there was concern that if this one was of the snail eating variety it might somehow harm the young Cahow chick. Alerted by our Twitter feed we woke up Jeremy who started preparing to go to the boat to rush out to Nonsuch to remove the worm, whilst in parallel we reached out to our partners at Cornell to review the high resolution footage of the intrusion.

Fortuntaley Cornell was quickly able to confirm from their higher resolution video that the worm could be seen exiting the burrow via the tunnel a few minutes after it arrived so the "crisis" was averted, nonetheless this is a very good example of how we can and should crowdsource our followers to help monitor these feeds. There were in fact many other never before documented incidents captured this season including an adult Cahow intruder that almost killed, our at the time, very young chick.

This year once "Shadow" fledged and the season officially wrapped up, we left the camera running to document what would happen to the nest after the Cahows left, and sure enough, as first documented last year, a very lost Storm Petrel moved in to make a nest and try to attract a mate. As much of this activity happens between midnight and 5 am our Citizen Scientist followers are again helping log his activities including a "battle" with two crabs that we might otherwise have missed.

For Second Year, Leach's Storm Petrel documented setting up nest on Nonsuch Island, broadcast live by CahowCam

2017 UPDATE at 3:15 am on June 13th during a thunderstorm "Stormy" returned to the Nonsuch Burrow, when he should be in the Canadian Maritimes.

See the 2016 News Alert:

June 18th 2016: The Cahow nesting season which is winding down, has thus far produced record numbers from the Nonsuch Island Colonies with 6 out of a total 10 chicks having fledged so far and is on track to produce the 2nd highest number of fledgelings from the whole colony, with 58, just down from 59 in 2014.

Recently named “Tempest” the star of the CahowCam livestream, attracted the largest audiences in the CahowCam’s 4 year history with over 6,000 viewers around the world watching live when he hatched and with 10’s of thousands watching his progress over the following 91 days.

J-P Rouja from the Nonsuch Expeditions Team said:

"This year we left the camera running after the chick had fledged on June 5th to see what happens immediately after the burrow is abandoned, and sure enough as happened last year within an hour a land crab made its way into the burrow to start feeding on the nesting materials.

To our utmost surprise however around 4 am a small petrel looking seabird first called into and then entered the chamber as if prospecting for a new nest site. This bird was less than half the size of a Cahow with a different vocal pattern so we knew it was something new. He spent about an hour rummaging around and then departed before sunrise leaving all of us who were watching online not sure what we had just witnessed and thankful that it had been recorded."

Chief Terrestrial Conservation Officer Jeremy Madeiros initially pointed us towards the Storm Petrel family, which is of the same nocturnal, burrow nesting tube nosed family as the Cahow, however none of these are known to have ever landed or nested in Bermuda, let alone be filmed doing so.

The Nonsuch Expeditions Team digitized the video and the audio recordings so that they could be shared amongst the local and international birding community experts and the consensus thus far confirms Mr. Madeiros’s suspicion that it is the dark rumped variation of a Leach’s Storm Petrel. These normally nest 800 to 900 miles away in the Canadian Maritimes and are less than half the size of Cahow with a wingspan of 19” versus 36” to 38” for a Cahow.

Jeremy Madeiros says:, "We all thought we had witnessed an amazing one off event, however the CahowCam has allowed us to witness two more 3.30am visits as this little bird who seems to be intent on occupying this nest and attracting a mate. The odds of this bird not only deciding to nest in Bermuda 800 + miles from home but also happening to pick the one burrow where we have a camera operating must be a million to one, but now that he is here there is actually the remotest possibility of him succeeding in attracting a mate as the species is known to feed in our open ocean waters.

This is a great gift for today, World Ocean’s day, as it shows that even as we increase our understanding, there is so much more to learn."

What is now evident is that through the ongoing successful management and protection of the slowly increasing Cahow colony there are other positive unintended consequences such as encouraging other species to nest here as well.

As of 4.30 am on June 8th “Stormy” as he is now nicknamed was sitting in the entrance of the recently vacated Cahow burrow on the edge of a cliff on Nonsuch Island calling out to sea for a prospective mate, whilst unknowingly connected to the digital world.

Please login to www.nonsuchisland.com/live-cahow-cam/ for replays and updates or watch live at 3.30 am or so tomorrow morning if you are awake and so inclined.

Best of luck Stormy on a rather stormy World Oceans day. :)

UPDATE: June 9th He visited again between 2 am and 4,30 am arranging the nest and calling out for a mate.

UPDATE: June 10th He is back again!

UPDATE: June 17th He is back yet once again! Virtually every night for the past 12 days!

Shadow the 2017 Cahowcam star has fledged!

On World Oceans Day the Nonsuch Expeditions and Cornell Lab of Ornithology Teams are pleased to announce that "Shadow" the star of the 2017 CahowCam successfully fledged out to sea on June 5th after exiting the burrow at around 11 pm.

Here is the last Video Health check and the naming of "Shadow"

Meet the 2017 Cahow Easter Chicks!

Jeremy Madeiros | As we prepare to celebrate Easter, I continue to be very encouraged and hopeful for the continuing recovery of one of the world's rarest seabirds.

As for the whole breeding population, the number of breeding pairs rose slightly to a record number of 117 pairs, up from 115 in 2016 (for those producing an egg, whether it hatched or not). The number of chicks at the present time (April 15th) is at least 62, although it is likely that we will loose at least a couple of those before they are ready to fledge to sea in late May/early June. Still, we have a good chance of breaking the present record of 59 fledged chicks in 2014 ( the number of successfully fledged chicks for last year's season (2016) was 56).

Perhaps the most encouraging statistic so far from this year's breeding season is that at least 9 to 10 new nests are being prospected by newly matured, young Cahows returning to the nesting grounds for the first time since fledging, with establishing pairs confirmed in most of them. Since most of these birds were fitted with identification bands while still in the nest, we know that they fledged to sea as chicks 3 to 5 years ago, and have since lived on the open ocean out of sight of land until their return this year. These potential new nesting pairs should hopefully produce their first eggs in the next breeding season in 2018 and come "on-line" as breeding pairs. As we prepare to celebrate Easter, I continue to be very encouraged and hopeful for the continuing recovery of one of the world's rarest seabirds.

The weight of the CahowCam R831 chick on Thursday was 302 grams, while the wing chord was 67mm (he was also fed again that night by the female bird, so obviously has gained weight again following that feeding).

April 13th Cahow health check Video

The CahowCam star chick is growing nicely!

Its' weight on Thursday the 13th of April was 302 grams, while the wing chord was 67mm (he was also fed again that night by the female bird, so obviously has gained weight again following that feeding).